April, 23 2016 – ARTLYST

The Herrick Gallery, London is currently presenting a selection of drawings by Francis Bacon and new paintings by Darren Coffield. It is stated that both artists create figuration with a twist: both manipulate the language of the human figure in art, reinterpreting the form through disturbing subversion.

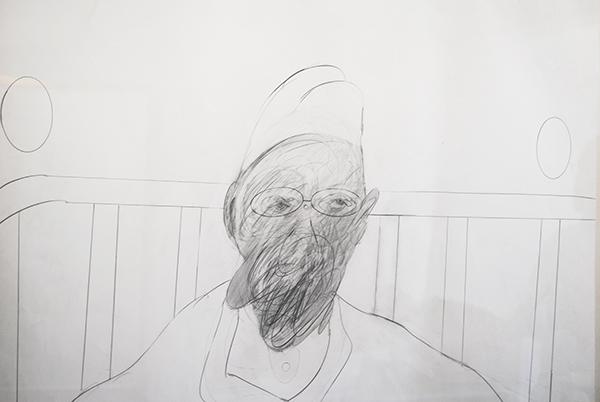

But there is another twist to this exhibition: the eight pencil & graphite drawings and two pastel collages said to be by Bacon, and gifted to his good friend in Italy, Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino, have had their authenticity questioned after previous drawings attributed to the artist were rejected as fakes by Martin Harrison, the author of the forthcoming catalogue raisonné of Bacon paintings, undertaken for the Francis Bacon Estate.

It is certainly true that the drawings and pastels employ many of the themes found in some of Bacon’s most iconic paintings, including the artist’s crucifixions, signs of Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, mingled with the Battleship Potemkin’s glasses and the occasional scream. These are large-scale pencil & graphite drawings on Fabriano paper, and also feature the artist’s trademark space frames often roughly hewn to demarcate and imprison the human form.

But there is a problem. Bacon fervently denied making drawings of any kind. Although as time has passed certain works have come to light, even including an exhibition of the artist’s sketches after Tate acquired a number of drawings by the artist and exhibited them in ‘Francis Bacon: Working on Paper’ in 1999. If studying photographs of Bacon’s Reece Mews studio, one soon notices torn-out images of diseases of the mouth, or the anatomical studies of movement by photographer Eadweard Muybridge, many sketched over with paint.

Francis Bacon expert Calvin Winner, Head of Collections at Sainsbury Centre For Visual Arts has stated that in fact the artist did sketch, the proof of which is to be found in his preparatory work on the canvas. This is Bacon sketching, it is all there in the artist’s unfinished canvases. But did Bacon ever create large-scale independent drawings on paper? One of the problems with these works is that there is literally nothing to compare them to.

Image: Darren Coffield, Leonard Cheshire i, 2015, acrylic on die-cut board. Photo: P A Black © 2016.

So how does one review an exhibition when the validity of half of the work on display is in question? Edward Lucie-Smith in his essay ‘Francis Bacon and the Act of Drawing’ reminds us that the idea of Bacon not drawing has become an article of faith with the majority of the artist’s most impassioned admirers. It is deeply embedded in their concept of what he was and did, although signs are coming to light that Bacon did draw on occasion, even if especially contentious, and denied by the artist – even if that denial was in fact an act of mischief to maintain the ‘magical existentialist shaman’s’ reputation.

The only way to review the work in juxtaposition with Coffield’s oeuvre is to suspend disbelief, even if temporarily. Both artists paths crossed when they met in the infamous Colony Room Club, in London’s Soho, in the late 80’s. Despite an age difference of sixty years, there is a commonality shared in the dissection and subversion of figuration. Bacon and Coffield were linked through David Sylvester, who was a fan of Coffield’s work, describing the artist as: “Another of those magicians who (probably without knowing) know how to imbue pieces of matter with light”.

In Coffield’s latest series of paintings the artist attempts to disrupt the viewer’s cognition; perceptions are manipulated – and much like Bacon – an attempt is made to disrupt the way the viewer processes the image, the figure is present and at the same time missing, broken, or disrupted. Both artists employ a subversion to disturb and provoke. The figure is framed, held in place, Bacon’s space frames were employed to trap the figure in the depths of existential angst, but also to control the focus of the work. Coffield frames his heads much like Bacon; there is no room to manoeuvre away from a direct physical confrontation. There is an equal intensity to the works’ focal points.

Both artists also employ a similar language structure where all information contained within the frame is still present, but the figure is ‘abstracted’ using its own constituent parts, this subject is corrupted by the re-ordering of its own elements. This process subverts viewer expectation resulting in ‘disturbance’. The viewer questions the physical nature of the image, the visceral mortality of the flesh is rendered subsumed. The image appears to absorb itself; Coffield understands Bacon’s language, the artist’s surfaces juxtapose neatly with Bacon’s malleable twisting forms.

‘I often think that I should [draw], but I don’t. It’s not very helpful in my kind of painting. As the actual texture, colour, the whole ways the paint moves, are so accidental, any sketches that I did before could only give a kind of skeleton, possibly, of the way the thing might happen’, as Bacon references the skeleton, one cannot help but wonder if drawing was in fact a skeleton in the artist’s cupboard after all.

Words: Paul Black © Artlyst 2016

Lead image: Untitled, (pope) (detail), grease pencil and graphite drawing, Fabriano paper (dry stamp) signed Francis Bacon. Photo: P A Black © 2016

Francis Bacon/Darren Coffield – Herrick Gallery, 93 Piccadilly, London – until 21st May