April 24, 2015

I remember viewing the exhibition ‘Francis Bacon: Working on Paper’, at Tate Britain in February 1999 with some scepticism. Bacon claimed that he never did preparatory work, didn’t draw, or make sketches before beginning work on one of his visceral creations. I really believed that these alleged snippets into Bacon’s apparently illicit practice of sketching might have been faked for some kind of financial gain. After all, an artist attempting to express the existential horror of living was likely to attempt this expression in the raw – at least that’s what I thought at the time, as an art graduate of a mere four years; and for Bacon the potential revelation that the artist did prep-work would surely weaken the public’s view of his painting? – like the magician revealing the trick.

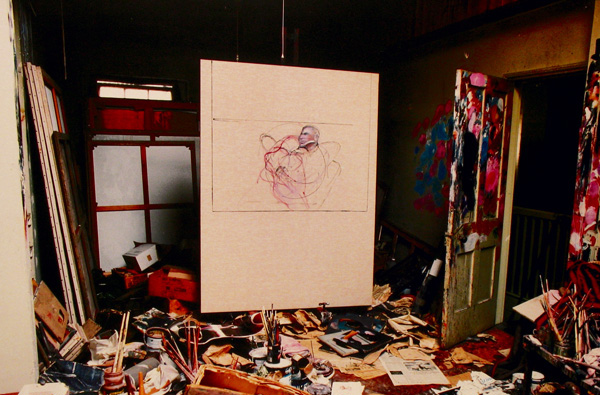

In a strange way it was almost impossible for Bacon to not have sketched out ideas, one only has to look at the photographs of the artist’s studio, or its impressive recreation in Dublin, to imagine the artist wading through heaps of reference material – the books on Velázquez, the torn-out pages from publications on diseases of the mouth, ripped photographs of men wrestling – the crumpled images by Eadweard Muybridge, or a lurid image of Henrietta Moraes posing for John Deakin’s lens. How could Bacon resist Sketchily painting into some of these images already stained with Pollock-esque splashes from the artist’s vigorous brush?

Well as it turns out – Bacon didn’t resist – as that particular exhibition at Tate Britain attested to at the time, even if he stated otherwise there was something ‘sketchy’ in the artist’s practice. The critic David Sylvester, one of Bacon’s loyal supporters wrote about the practice of drawing in 1954: ‘A painter or sculptor who has not the habit of making drawings is considered a curiosity.’ Some eight years later the critic posed the question to Bacon: ‘you never work from sketches or drawings, you never do a rehearsal for the picture?’ Bacon’s response was unequivocal, ‘I often think I should, but I don’t. It’s not very helpful for my kind of painting. As the actual texture, colour, the whole way the paint moves, are so accidental, any sketches that I did before could only give a kind of skeleton, possibly, of the way the thing might happen.’

The statement is a curious one considering that the existence of a certain work was already known by Bacon Scholars; ‘Figure in a Landscape’, 1952, was a work on paper, a drawing to be exact, which the artist subsequently gave to his friend Stephen Spender, possibly during the early 1960s. But the statement went unchallenged, and Bacon’s insistence remained unquestioned.

It was in fact only upon Bacon’s death that even greater light was shed on the nature of the artist’s practice regarding drawing and sketching. Bacon not only left the glorious creative mess of his studio at 7 Reece Mews, but also a number of unfinished paintings. These were a revelation, and shed light on the early stages of the artist’s painting process. The works were in fact all the more revealing in light of Bacon’s particular practice of destroying large quantities of unfinished works that he deemed unsuitable to remain within his oeuvre. The absence of unfinished work had always prevented anything other than fully formed paintings being seen by anyone other than the artist himself. But now there were unfinished works to be studied and the nature of Bacon’s practice was now seemingly quite obvious.

Image: An unfinished canvas was on an easel when Bacon Died, first thought to be a self-portrait, it actually resembles Bacon’s lover George Dyer, and now resides in the collection of the Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin.

Artlyst spoke to Calvin Winner, Head of Collections at Sainsbury Centre For Visual Arts, and co-curator of ‘Francis Bacon and the Masters’, to give us his opinion of Bacon’s process in relation to the artist’s unfinished work ‘Three Figures’ – one of three incomplete paintings in the exhibition.

“The question of whether Bacon sketched – because famously he didn’t sketch, he didn’t make preparatory drawings – and the reason of course is that his preparatory work is on the canvas. This is Bacon sketching, this is Bacon drawing, it’s all here in these unfinished canvases, so he would approach the bare canvas with the skeleton of a preparatory work, and then begin to fill in spaces, and I think on the centre work [Three Figures] we can already see some of his characteristic motifs, the great arcs that he would paint, the boxes: the so-called space-frames that he would place around figures – it’s all beginning to be put in place – but we don’t know why these works were unfinished. He kept them in his studio, he didn’t destroy them, they were obviously useful to him. So again, there’s this idea that his preparatory work was directly on the canvas – he saved these because he was presumably finding them of use for the future – it’s a real window into the artist’s technique and his studio practice.”

So Bacon’s working process differed from other artists principally in seeking to suppress the existence of drawing as part of the artist’s preparation for painting, whether early in his career on paper, or later directly on the canvas. It’s obvious that art historians opinions still differ on the subject. But it could be said that the denial of drawing fits with ‘Bacon the autodidact’, that he wished to convey the spontaneity of the self-trained artist. In fact it’s entirely possible that Bacon believed that the existence of preparation for his visceral onslaughts would somehow detract from the authenticity of the final paintings – that somehow their rawness would be tempered in the eye of the viewer – the magician would have given away his secrets, and the magic would lose its wonder. For Bacon sketching was not only a skeleton on the canvas, but it would seem, one in the cupboard as well.

Words: Paul Black and Calvin Winner © Artlyst 2015 all rights reserved