July 22, 2016 – ARTLYST

I was recently in Trieste, for a small exhibition of drawings attributed to Francis Bacon. This can hardly be considered a review, as my links to the whole Bacon drawings controversy are already well known and in the public domain. Francis Bacon always denied that he made drawings. In this, as in quite a number of other aspects of his life, he was provably a liar. Since his death, a very considerable body of drawings has emerged, from a number of sources.

There are the drawings found when Bacon’s Reece Mews was taken apart, piece by piece, for re-assembly in Dublin. There are those which finished up in the hands of Bacon’s friend and friendly odd-job man Barrie Joule. Joule presented those to the Tate, where they remain in a kind of limbo – part of the Tate archive, but not registered as ‘art’. There are smaller groups of drawings with Tate – some came from the widow of the poet Stephen Spender, some from Bacon’s friend, the actor Paul Danquah (later a consultant with the World Bank in Washington). Bacon once shared a flat overlooking Battersea Park with Danquah and his partner Pete Pollock, and later visited them in Tangiers. These two minor groups Tate accepts as legit.

There are no major differences between the Danquah drawings and the much bigger series donated by Joule. Tate purchased them in 1996, and exhibited them, under Bacon’s name, with no attendant qualifications, in 1999.

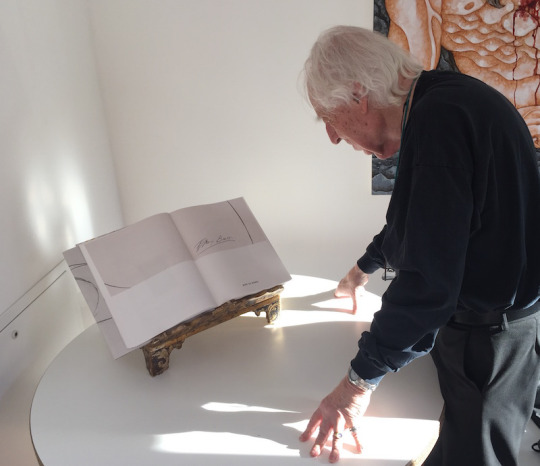

The big series of drawings belonging to the Italian journalist Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino are a slightly different matter. They are all signed, quite a few are in colour, including some which are quite elaborate collages. And most of them are recapitulations of themes that preoccupied Bacon earlier in his career – there are Popes and Crucifixions, for example. Ravarino acted as Bacon’s young boon companion and cicerone. They met at the Villa Medici in Rome but their revels were mostly in Bologna, Ravarino’s city of residence, and in Cortina d’Ampezzo. Their presence together in both of these places is attested by quite numerous Italian witnesses, some testifying under oath in an Italian court, when Ravarino was accused of selling forgeries (and duly acquitted).

In my view – but I stress that this is a personal view – these often moving late drawings show Bacon meditating about themes that had preoccupied him at the beginning of his career. He is on record as expressing doubts about his Pope paintings (derived from Velazquez’s famous portrait of Innocent X in Palazzo Pamphilij in Rome), which initially made him famous. Here he was perhaps for once telling the truth. As an untrained, totally autodidactic artist, he never seems to have been completely sure about his own gift. Hence all the lying and myth making.

It’s not necessary for a major artist to be a man of good character. Caravaggio offers an earlier case in point. I think he and Bacon might have had a thing or two to say to one another. For example, about their mutual taste for handsome young men, something fiercely disapproved of in the otherwise very different societies they lived in.

The small selection of drawings on show at Porto Piccolo, a gated holiday resort on the coast near Trieste – a colorful Pope, a group of Crucifixions -were, to me, a reminder of how powerful Bacon could be, when working in secret, more or less entirely for himself.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photos P C Robinson © Artlyst 2016

360˙ Gallery Tour By P C Robinson and Daniel Bourke To operate click on arrows in upper left hand circle.