For this specific case, I will focus on the relation Francis Bacon (1909-1992) had with the action of drawing, something that can be deduced from his direct words

– “I do not make sketches nor drawings. I just proceed”.

– “I love drawings but I do not draw”.

– “…I have never drawn: however, my painting is pretty much characterized by drawing”.

These statements are clear-cut but not deprived of any ambiguity, as we will see later on. Bacon indeed seems to expel the art of drawing from his artistic world, even if this represented his first creative expression since he started to work as an interior designer in the „30s.

When Bacon affirmed himself as a painter, nobody knew nothing about his drawings; it was even said he did not draw at all…

However, on December 1992, soon after his death that took place on April 28th 1992, a preparatory sketch for the painting “Study of a nude” of 1954 appeared at an auction.

In June 1996, the posthumous retrospective “Francis Bacon” organized at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and curated by David Sylvester, considered as the main interpreter of the Anglo-Irish artist, included some sketches, gouaches and notes on pictures even if the Catalogue underlined how these works were not aesthetically nor technically easy to locate in relation with the paintings.

In 1997, the widow of the poet and essayist Stephen Spender, one year after his death, sold some small-scale drawings to the Tate Gallery, works donated by Francis Bacon to his friend Stephen in the „50s.

On February 14th 1999, the Tate Gallery in London inaugurated the exhibition

“Francis Bacon Working on Paper”. Matthew Gale, the curator, collected works purchased by the Tate itself with the funds of the National Art Collections Fund, works taken from the collection of the English poet Stephen Spender and others owned by Paul Daunquahl, lawyer, actor and financial advisor with whom Bacon shared his apartment in 1959.

The Tate Gallery, Bacon‟s preferred gallery, came into play with all its importance, as well as David Sylvester who, in the introductory essay to the Catalogue, openly confessed he always knew that Francis Bacon drew; actually, the artist drew a lot but he intentionally lied on this to respect the artist‟s will. Therefore, Sylvester admitted for the first time that Bacon did not tell the entire truth on the issue of drawing, that his closest friends knew it and that the existence of some works represented just the tip of the iceberg.

Always on February 14th 1999, Barry Joule, Bacon‟s neighbour and handyman, showed a corpus of graphic findings made up of approximately 1200 items retrieved in the studio the artist had in London, i.e. pictures and book pages that were sketched, stained, decorated as well as other sketches and outlines. During a TV interview, Joule remembered that Bacon, ill and old, told him to remove the paper works he had in Reece Mews‟ studio by saying “You know what you have to do with them, don’t you?” Enigmatic sentence this one, typical of the Baconian‟s style, as if he wanted to pass on to somebody else a lit match and Barry Joule indeed did not destroy anything.

After many legal disputes between Barry Joule and the lawyers representing the Estate managing the artist‟s property, more than 1200 items coming from Bacon‟s studio were purchased by the Tate Gallery as a donation, that is why these works today are not recognized as authentic but only as “works attributed to Francis Bacon”.

After finding this graphic production, several experts expressed their points of view in different ways: either they praised it or they were sceptical. In my opinion, here we have a first ambiguity in terminological terms that is clarified by the Italian art critic Giorgio Soavi and the journalist Alessio Altichieri in an article on the newspaper “Corriere della Sera” of March 26 1999.

– “As a matter of fact, drawings are not really drawings, but more like improvised sketches, five or six brush-strokes of oil paint on a sheet of paper.” Soavi continues “…even flies would not be so thrilled with them“.

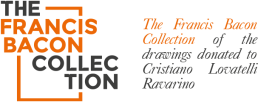

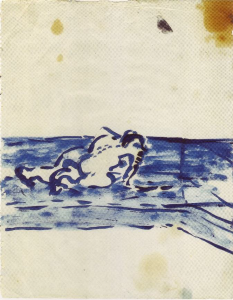

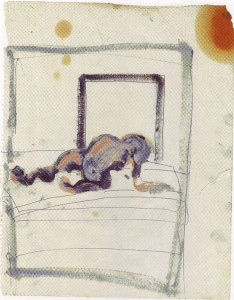

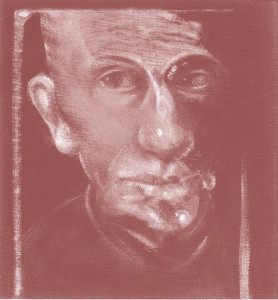

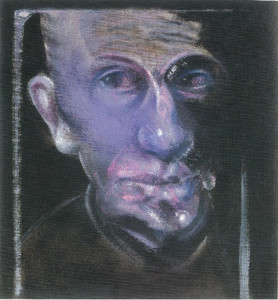

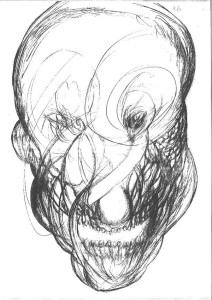

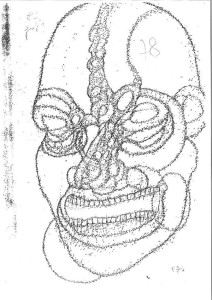

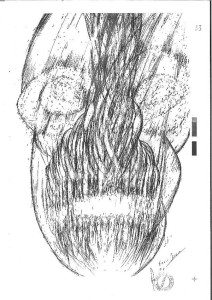

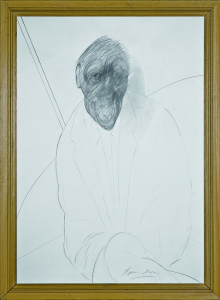

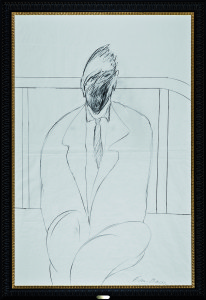

(figures 1, 2, 3)

Stop calling drawings what in reality are just sketches and outlines, or even scribbles.

Therefore, where are Bacon‟s drawings that David Sylvester defined as the tip of the “Bacon” iceberg; that the biographer Michael Peppiat saw and declared that not all of them were destroyed. Where are the drawings that Horacio de Sosa, his Argentinian friend, painter, regularly saw in Bacon‟s studios, both in Paris and in London; where are the drawings that, according to the journalist-writer and friend Daniel Farson, were in circulation. Where are the drawings that the sculptor Alberto Giacometti saw after visiting Bacon‟s studio in London, and wrote to a friend that he did not particularly like Francis‟ painting but preferred his drawings.

And especially, where are the two “beautiful portraits” of the poet Stephen Sender, donated and “drawn in pencil by Francis Bacon” that the journalist and writer Gaia Servadio, friend of the Spender‟s family, mentioned on her article published on page 25 on the Italian newspaper “Corriere della Sera” on July 18th 1995 on the occasion of the poet‟s death. Servadio also underlined how these drawings made by Bacon were in “good company” with other donations made by other artist friends, such as Vanessa Bell‟s landscapes (Virginia Woolf‟s sister) or as Henry Moore‟s bronzes.

Drawing remains an aspiration for many artists, of any time and belonging to any art movement, it probably happened the same thing with Bacon; this desire indeed can be continuously perceived in his interviews where he mentioned with great admiration, if not even with envy, the drawings by Giacometti, Rembrandt, Degas, Ingres, Picasso an Michelangelo.

It is thus reasonable to think that drawing might have been Bacon‟s aspiration as well, on which he probably saw some limits that led him to choose oil colours, which simplified smoothness and unpredictability. The sentence “my painting is pretty much characterized by drawing” can thus acquire a specific meaning since oil painting allowed him a direct and essential drawing planning as well as a greater control of all somatic details in portraits, to which a deformation phase followed, to comply with his principles.

Indeed, the talent of Francis Bacon became genius when he built up a painting aesthetics that was extremely personal, inimitable and especially non-explanatory, not abstract, deformed but with a strong figurative impact, thus opening a “third way” of expression to modern painting.

Bacon gave detailed information about his artistic approach and certainly clarified what could have been the spaces of his creativity, but also kept some grey zones such as that related to drawing.

Bacon‟s constant commitment was to move away from the real somatic elements of the character, but since the way we act usually corresponds to the way we are, this happened in some way to our artist as well. Some lapsus pictoris escaped his control unveiling the executive mode that Bacon would have liked to hide since he expected only the utmost products to come out from his atelier.

Just think about the training that Bacon did on drawing over time.

In his pastel self-portrait of the „30s, which is therefore a drawing, the technique

used is self-taught with a formal, conventional result, almost academic, showing even a poor ability in distributing the colour due to a lack of light and shade effect that creates a thick and clownesque result.

The oil and pastel painting of 1944, “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion”, which established a new artist profile, was not yet subject to the settling and layering of oil paint since Bacon deformed faces while drawing. The brush-stroke here is not seen as a “creative accident” or as a consequence of colour moving.

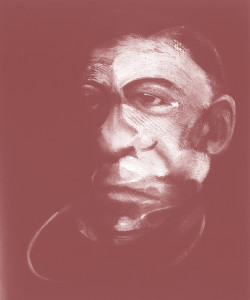

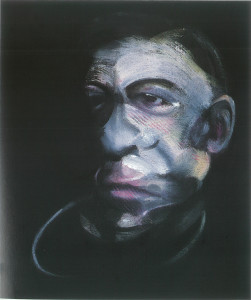

In oil portraits or self-portraits after the „60s, the typically Baconian deformation of somatic characteristics is now present even if with some exceptions, we will never know if intentional or unintentional, that convey a formal, academic outcome, which was exactly what Bacon did not want. On the contrary, the non-deformed faces or part of them are tinged with a realistic, cartoon stylistic method typical of the American Super Hero, with a deep illustrative outcome.

As for the use of colour, in the parts that were not deformed, one can perceive de Maistre‟s influence: many chromatic differences, if oil paint and brushes are used, were gathered under a strong and layered texture interfering and limiting the status of static decorative effect without removing it entirely.

For sure, Bacon would not have liked the association of his faces or part of them with cartoons, even if this fact is objective and tangible as if Bacon acquired by assimilation a cinematographic “frame rate” of his time.

Indeed, by adapting a slightly deformed image to a mono-tone colour by using Photoshop CS6, as if you were using graphite, pastel or sanguigna, the original Baconian drawing mark comes out, even if hypothetically: kicked out from the door, it entered again from the window thus conveying a drawing effect that was exclusively illustrative, what Bacon would have never wanted

(figures 4-5)

(figures 6-7).

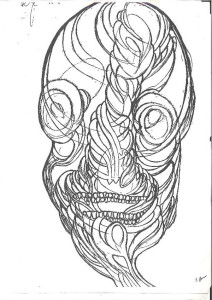

A further Baconian enigma is the “corpus” made up of the so-called “Italian” drawings, donation that Bacon made to his good friend and lover Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino: from the technical and aesthetical point of view, they are neither in contrast with his biography, nor with his theoretical imprinting. One might not exclude that these “Italian” drawings represent the only way out that allowed Bacon to revise and readapt his painting technique.

The Italian drawings indeed are drawings in all respects, neither sketches nor outlines, they are anti-illustrative, they are not abstract and are strongly figurative, they tend to deformation but they are not caricatures, and they do not recall a naive style nor a cartoon one.

The use of the “tachistes” technique exalted by Bacon since the „50s is evident in the small-scale “Italian” drawings, almost in an obsessive way. It is a real graphic syntax made up of a sequence of incisive and penetrating micro-strokes or by long, overlapping lines thin as hair.

(figure 8)

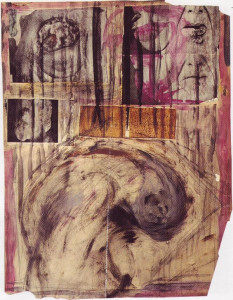

In medium-size “Italian” drawings, the artist often used the collage technique leading us to the “papiers collés” Picasso liked so much. It is the largest set of drawings where the almost automatic repetition of many images does not represent a mechanical action because images live a life of their own, being always specifically conceived and never imitated

(figure 9)

All large-scale drawings, more than two meters, are compatible with sculpture in terms of structure. Indeed, this indomitable seventy-year-old artist told his friend Sylvester since the beginning of the „60s that he would have liked to create some sculptures, ambition which pushed him to describe in detail its technique and implementation, even if he never applied them for real.

(figure 10)

The hand that made these “Italian” drawings is unique, showing a personality that cannot be limited, with artistic desires aimed at coming out of a circle. It is almost a revenge against a Court of friends and patrons who competed to embrace their Lord with what was said and what was unsaid, of a merchant, the Marloboruygh Gallery, which always claimed that Bacon did not draw and if he drew, he would have destroyed such drawings.

Therefore, we have to accept the existence of this large “corpus” of “Italian” drawings that Francis Bacon donated to his friend and lover Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino in his last fifteen years of life.

AMBRA DRAGHETTI (graphologist)

Figures 1-2-3 – from the Tate Gallery and from The Barry Joule Archive – Irish Museum of Modern Art -Year 2000

Figures 4-5 –Two studies for Portrait of Richard Chopping 1978 – from Bacon Portraits and Self- Portraits Milan Kundera – France Borel – Thames And Hudson -1996

Figures 6-7 –Portrait by Jacques Dipin 1990 – from Bacon Portraits and Self-Portraits Milan

Kundera – France Borel – Thames And Hudson -1996

Figure 8- Drawings owned by Mr. Cristiano Lovateli Ravarino and presented in 1981 (Bacon was still alive) to the exhibition “Francis Bacon” – Galleria d‟arte Nanni – Bologna

Figure 9 and figure 10- from Work on paper – A Catalogue of the Drawings by the Artis Donated to Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino – TFBC -The Francis Bacon Collection of the drawings donated to Cristiano Lovatelli Ravarino.